Mount Hood climbing accidents

Mount Hood climbing accidents are mountain climbing- or hiking-related incidents on Oregon's Mount Hood. As of 2007, about 10,000 people attempt to climb Mount Hood each year.[1] As of May 2002, more than 130 people have died climbing Mount Hood since records have been kept.[2] One of the worst climbing accidents occurred in 1986, when seven teenagers and two school teachers froze to death while attempting to retreat from a storm.[2]

|

Despite a quadrupling of forest visitors since 1990, the number of people requiring rescue remains steady at around 25 to 50 per year, largely because of the increased use of cell phones and GPS devices.[3] 3.4 percent of 2006's search and rescue missions were for mountain climbers. In comparison, 20% were for vehicles (including ATVs and snowmobiles), 3% were for mushroom collectors, the remaining 73.6 percent were for skiers, boaters, and participants in other mountain activities.[4]

Hazards

Cascade Range weather patterns can be deceiving, with sudden sustained winds of 60 miles per hour (100 km/h), and visibility quickly dropping from hundreds of miles to an arm's length; climbers can experience 60 °F (33 °C) temperature drops in less than an hour after leaving an access point. This pattern is responsible for the most well known incidents of May 1986 and December 2006.[5]

Avalanches are popularly regarded to be a major climbing hazard, but relatively few Mount Hood deaths are attributed to them. For the 11-year period ending April 2006,[6] there was one death on Mount Hood caused by an avalanche,[7] while 445 avalanche-related deaths occurred throughout North America.[8] Compared to other western states, Oregon has the fewest avalanche fatalities.[9] Worldwide, between 100 and 200 people die each year from avalanches.[10]

The two major causes of climbing deaths on Mount Hood are falls and hypothermia.[11][12]

Incident history

From 1890 through 1990

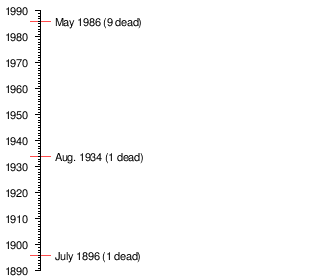

According to Mount Hood: A Complete History by Jack Grauer, the first recorded climbing fatality on Hood's slopes occurred on July 12, 1896, when Frederic Kirn eschewed his guide and attempted the trip to the summit alone.[13] Kirn's body was found on the Newton Clark Glacier on the east side of the mountain, after an apparent 40-story fall in connection with an avalanche.

In an unusual accident reported in Grauer's book, on August 27, 1934, Victor Von Norman successfully climbed the peak via the southern route, along with a group of fellow University of Washington students. He then ventured too close to a fumarole between Crater Rock and the "Hogsback" that connects Crater Rock with the summit ridge, was overcome by oxygen-barren gases emanating from the fumarole, and fell about 50 feet (15 m) to his death. A number of men who tried to retrieve the body were also nearly overcome by the fumes before finally succeeding in their efforts.[14]

On March 1, 1969, James Eaton died when he fell head first into a concealed 60 foot crevasse near the edge of the upper portion of the White River Canyon. Eaton was ski instructor and a member of the Mt. Hood Ski Patrol.[15]

Beginning on New Year's Eve in 1975, two 16-year-olds and an 18-year-old survived in a snow cave 13 days through a snow storm.[16]

On May 19, 1980, Tom Hanstedt died while descending the mountain's southeast face, falling deep into a crevasse on the Newton-Clark Glacier. His body was never recovered.[17]

On June 6, 1981 David H. Turple and Bill Pilkenton died in a fall from Cooper Spur on the northeast side of the mountain.[18]

On June 21, 1981 five members of the Mazamas climbing group died during a fall from Cooper Spur while descending.[18]

One of the worst U.S. climbing accidents occurred in May 1986 when seven students and two faculty of the Oregon Episcopal School froze to death during an annual school climb.[2] Of the four survivors, three had life-threatening hypothermia; one had legs amputated.[19]

On July 11, 1987 Arthur Andersen Jr. was killed when he and two other men fell on the south side of the peak and slid into a crevasse.[18]

In June 1990 William Ott died from hypothermia on the mountain. Ott's widow was not surprised to learn of her husband's fate. She said she had not expected her husband, who had terminal cancer, to return from the trip he had chosen to make by himself.[18]

Since 1990

On September 25, 1995 Kenneth Budlong, 45, of Portland attempted to climb the peak via the Cathedral Ridge route. Budlong was very experienced, having summited the peak 22 times before. However, the weather turned very quickly, and Budlong vanished. Despite an extensive search over the following days, his whereabouts were never determined, and his body never found. [20]

On May 19, 1997, a solo climber summited successfully with his dog, Buckwheat. While descending Coe Glacier he slipped and fell 700 feet (210 m), fracturing his neck. After being reported overdue by family, rescuers found him with facial lacerations, slight hypothermia, and cervical trauma. He was treated and helicoptered to Portland, but Buckwheat was not at the scene. A month later, the dog appeared at Cooper Spur Inn, some 9.4 kilometres (5.8 mi) ENE across the rugged Mount Hood Wilderness, evidently having survived on snow melt and berries.[21]

On September 6, 1997, an experienced telemark skier, Mark Fraas of Hood River, ascended wearing crampons and carrying skis to the 10,000-foot (3,000 m) level of Cooper Spur, not intending to summit. He slipped and fell more than 1,500 feet (460 m) down the Chisholm Trail and Eliot Glacier. Twenty-five rescuers responded to his partner's cell phone call and found him dead. Retrieval required technical mountaineering skills and equipment. Fraas was not known to have any climbing experience. This was at least the 13th fatality from Cooper Spur. All involve loss of footing, inability to self-arrest, and a long fall over rock cliffs above the Eliot Glacier.[22]

On May 31, 1998 during a graduation climb for The Mazamas mountaineering club, several were caught by an avalanche. One died, one had serious injuries.[23] The climbers were at the 10,700-foot (3,300 m) level on the West Crater Rim route; the forecast was for "significant avalanche danger" and was posted "high avalanche hazard" at Timberline's climbing registration. A large slab avalanche fracture occurred at the 10,800-foot (3,300 m) level, 200 feet (60 m) vertical below the westernmost summit ridge. A roped team of three were swept down the steep slope through the Hot Rocks area. One was killed by injuries during the fall and found under four feet of snow about an hour later. The other two climbers had a fractured pelvis, and fractured ankle, respectively. The leader, who was only briefly caught by the avalanche, had injuries to an ankle and shoulder.[24]

On May 23, 1999, an experienced pair of climbers summited successfully. Shortly after commencing their descent, one stumbled and both fell more than 2,000 feet (610 m) to their deaths.[25]

On June 22, 1999, a 24-year-old medical student from Michigan apparently set out from a remote trailhead where his rental car was found. Temperatures dropped 15 degrees and more than an inch of rain fell beginning the next day. Ten days after his presumed disappearance, searching began with up to 70 rescuers combing the area. Additional searches included cadaver dogs and psychics. No sign of him was found.[3]

On September 8, 2001, rescuers abandoned a search for a 24-year-old Hungarian exchange student who had been missing for six days. He had been hiking with friends when he left the group with light clothing and no provisions. Two days after his disappearance, the weather turned cold and snowy.[26]

On May 24, 2002, a 30-year-old Argentine national attempted to snowboard off Mount Hood's summit along Cooper Spur ridge. He lost control after a few turns and tumbled over 2,000 feet (610 m) to his death.[27]

On May 30, 2002, three climbers were killed and four others injured when they fell into a crevasse (The Bergschrund) in the "hogsback". Most unusual was the televised crash-and-roll of a USAF Pavehawk rescue helicopter from the 304th RQS which suddenly lost lift.[28]

On March 7, 2003, the search for a man snowshoeing from Timberline Lodge was abandoned after more than four days in heavy winter weather. More than six feet of snow fell during the search.[29] An extensive search five months later for the man's body failed, but unexpectedly discovered the body of another man who was not identified.[30]

On Thursday, December 7, 2006, three experienced climbers—Kelly James, Brian Hall, and Jerry "Nikko" Cooke—began what they expected to be a two-day expedition on the more-treacherous north slope of the mountain. On Saturday, December 9, 2006, the climbers failed to meet a friend who was scheduled to pick them up at Timberline Lodge.[31] On Sunday, December 10, 2006 James made a cell phone call to his wife, and two older sons telling them that he was trapped in a snow cave and Brian and Nikko had gone for help.[32][33] Rescue attempts were forestalled by freezing rain, heavy snowfall, low visibility and winds of 100 to 140 mph (160 to 230 km/h), caused by a widespread winter storm. Clear weather on the weekend of December 16 allowed almost 100 search and rescue personnel to scour the mountain. On Sunday, December 17, searchers found what they first believed to be a snow cave and climbing equipment, approximately 300 feet (90 m) from the summit.[34] At that location, the rescuers found a rope, two ice axes and an insulating sleeping pad. At approximately 3:29 PM PST, the body of Kelly James was found in another snow cave near the first one. On Wednesday, December 20, 2006, as good weather ended, the Hood River County sheriff announced that the mission was now being treated as a recovery rather than a rescue.[35] Brian Hall and Jerry Cooke remain missing and have been declared dead.[36]

On the morning of Saturday, February 17, 2007, eight experienced climbers from the Portland area ascended in sunny, mild weather. Observing worse weather mid-afternoon, they camped at the 9,300 feet (2,800 m) level of Illumination Saddle overnight. Sunday morning, they abandoned a summit attempt and descended in freezing rain and snow, visibility less than 30 feet (9 m), and winds at 40 to 70 mph (64 to 120 km/h). At about noon, disoriented, three of the climbers and a black lab stepped off a cliff (at the 8,300 ft (2,500 m) level at the east edge of Palmer Glacier) while tethered together and tumbled down several hundred feet of steep slope into White River Canyon. One of the remaining five climbers was lowered by rope to search for the fallen group, but returned without seeing them. They called for help by cell phone, and were advised of even worse weather advancing, so dug in expecting another night. However, rescuers arrived and evacuated them Sunday evening. The three fallen climbers were unable to dig into solid ice to build a snow cave, so they improvised a shelter and were in hourly cell phone contact with rescuers. They had a Mountain Locator Unit, sleeping bags, GPS, and a tarp. The dog, Velvet, helped keep them warm. Rescuers arrived Monday about 10:45 am. One was hospitalized for a head injury, the others were treated for minor injuries and released. The dog had broken nails and a cut on one of her back legs from cold exposure.[1][4][37][38]

On May 12, 2007, five climbers were stranded at the 9,400 ft (2,900 m) level by whiteout conditions. The climbers contacted rescuers by cell phone and obtained assistance to navigate to Illumination Saddle, on the south side of the mountain. Using their GPS navigation unit, the climbers traversed to the saddle and descended the mountain without further incident. The climbers carried a Mountain Locator Unit with them, which would have allowed rescuers to pinpoint their location, had they not been able to descend from the mountain on their own.[39]

On September 7, 2007, two Portland-area climbers were ascending a technical approach to the Pearly Gates at early afternoon when one slid to the edge of the Bergshrund and sustained injuries sufficient for him to call for rescue assistance. His partner decided it was too dangerous to descend the frozen gravel and loose rock face and remained in place. Rescuers arrived about five hours later, assessed the fallen climber, treated minor injuries and belayed him walking down. The other climber required technical climbing equipment and was assisted down the Bergshrund. He walked down and joined his partner about dawn at a Timberline snowcat at the top of the ski area.[40]

On January 14, 2008, two young experienced climbers intended to ascend the Leuthold Couloir route (above Illumination Rock) and began in good weather. When their return was overdue that afternoon, a search and rescue team activated for the following morning, but was turned back by bad weather. At 9 am, cell phone contact was established and rescuers learned they spent the night below the tree line. Rescuers escorted them out two hours later.[41] The climbers were unprepared for bad weather which arrived as they reached the 10,000 ft (3,000 m) level. Thinking they had a clear weather window, they had no GPS, nor Mountain Locator Unit, and did not believe their cell phone was usable. Descending with a map and compass, they navigated southward hoping to encounter Timberline Lodge, Government Camp, or the Mount Hood Highway. Not finding any of these, they reached the 5,000 ft (1,500 m) level and built a snow cave to spend the night. In the morning, they inadvertently discovered a geocache labeled with coordinates just as a rescue sheriff called their cell phone.[42][43]

On October 19, 2008, an inexperienced solo climber fell as he began his descent after summitting. His crampons slipped leading to an uncontrolled slide of about 300 feet (90 m) vertical near Crater Rock. He was unable to arrest his fall using an ice ax, and blacked out after his head struck the surface. Another climber witnessed his fall and rushed to assist, observed head trauma and confusion, and called for help using a cell phone, then descended to meet rescuers. A third climber remained with him until help arrived since the victim was unable to descend on foot. Rescuers arrived a few hours later, applied first aid to stabilize, and called for air evacuation to a Portland hospital. He was treated for cuts and scrapes, and released.[44][45][46][47][48]

On January 17, 2009, a search and rescuer on a training exercise was injured when the ice he was climbing collapsed causing him to fall some 200 feet (60 m) resulting in severe ankle injuries. Another team member was injured, but was able to walk down. Another rescue team was practicing in the area at the time and assisted the first team.[49]

On January 21, 2009, a climber died after a temperature inversion likely loosened ice from cliffs above the Hogsback. She tumbled 400 feet (120 m) before stopping in a natural depression.[50]

On February 1, 2009, two men were ascending the Hogsback. Fatigue and poor weather caused them to abort a summit attempt and descend. One lost his balance and fell some 20 feet (6.1 m) before self-arresting, during which he dislocated a shoulder. The other climber called 911 and initiated assistance. Another group of climbers stopped and helped walk the injured climber to the Timberline Ski Area where a snow cat with rescuers awaited.[51]

On May 17, 2009, a climber received severe injuries to his face, arm and leg in a 500-foot (150 m) fall at the 10,600 level of the Hogsback. At least 40 climbers were attempting to summit at the time. The previous day a climber in a group of ten was struck by falling ice. Both climbers were hospitalized.[52]

On December 13, 2009, rescuers recovered the body of 26-year-old Luke T. Gullberg, of Des Moines, Washington, at about the 9,000-foot level, two days after the trio began climbing an especially treacherous face of the mountain.[53] On August 26, 2010, after several days of a renewed search effort, Portland Mountain Rescue recovered the bodies of Anthony Vietti and Katie Nolan, still tied together.[54]

On June 16, 2010, five climbers with ski gear hiked up Snow Dome, a popular wilderness back country area on the north side, intending to ski down. Bad weather rolled in causing poor visibility and strong winds. One climber, Robert Dale Wiebe from Canada, was separated and accidentally traversed Coe Glacier where he apparently fell 700 feet (210 m) to his death.[55][56]

On July 7, 2010, a 25 year old male climber had successfully summited. During the initial descent, he lost footing near Hot Rocks and was unable to stop, injuring his knee and elbow. Nearby climbers provided first aid until rescuers and paramedics arrived and stabilized him. He was loaded into a sled and lowered down with an improvised arrangement of rope and pulley systems.[57]

On July 24, 2010, a 54 year old male from Arizona fell from the Hogsback and fractured or dislocated an ankle and received abrasions from sliding down granular ice. The victim was airlifted to a Portland hospital.[58]

On January 22, 2011, three friends summited successfully in the afternoon, but one broke his crampon during descent. At 5 p.m., his partners continued down without him separating from him at Crater Rock. They notified authorities when he did not return, reporting he lacked a light and overnight gear though he had "a beacon" from REI, but did not know what it was, but said he would "pull the knob" if something happened. The sheriff called for search assistance, and since Portland Mountain Rescue was already in the area for a winter bivouac exercise, they conducted an MLU search at 8 p.m. and quickly identified a signal from White River Canyon. It was a clear night near freezing with winds at 20 miles per hour (32 km/h). Night ski lighting from Skibowl and Timberline was clearly visible when they located the victim east of Palmer Glacier at 7,700 feet (2,300 m) around midnight in light garments. They treated with warm clothing, liquids, and heat packs and took him back to Timberline.[59]

Late on February 20, 2011, a snowboarder was reported lost on Mount Hood. Initial information and cell phone tracking indicated he was northwest of Zig Zag Canyon. Five searchers were unable to find him that night though visibility improved during the evening. The next morning had better conditions and involved many more searchers. He was found by a National Guard helicopter which airlifted him to Timberline Lodge, cold but in good spirits. As rescuers were debriefing with a sheriff, a call for assistance arrived from a 13 year old male snowboarder who was out-of-bounds below the Timberline Ski area. He was found within 20 minutes of the call, given hot drink and food, and escorted to Timberline's first aid room.[60]

References

- ^ a b Aimee Green, Mark Larabee and Katy Muldoon (February 19, 2007). "Everything goes right in Mount Hood search". The Oregonian/OregonLive.com. http://blog.oregonlive.com/breakingnews/2007/02/everything_goes_right_in_mount.html. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ a b c "Last Body Recovered From Mount Hood". CBS. May 31, 2002. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/05/30/national/main510637.shtml. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ a b Nigel Jaquiss (October 13, 1999). "Without A Trace". Willamette Week. http://www.wweek.com/html/leada101399.html. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ a b Kristi Keck (February 20, 2007). "Weighing the risks of climbing on Mount Hood". CNN. Archived from the original on 2007-02-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20070222103839/http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/02/19/hood.rescue/index.html. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ See incident summary references.

- ^ The statistical period of the Westwide Avalanche Network is 31 December 1994 to 30 April 2006, almost eleven and a half years.

- ^ "Oregon - Avalanche History". Oregon Mountaineering Association. http://www.i-world.net/oma/avalanche/avalanche-history.html. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ "Previous Season Avalanche Accidents". Westwide Avalanche Network. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20060928065031/http://www.avalanche.org/accidnt1.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ "U.S. Avalanche Fatalities by State 1996-2002". Utah Avalanche Center. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20060928072741/http://www.avalanche.org/~uac/graf_fatestate.html. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ "Avalanche Fatalities in IKAR Countries 1976-2001". Utah Avalanche Center. Archived from the original on 2006-11-04. http://web.archive.org/web/20061104004109/http://www.avalanche.org/~uac/graf_world_ava.html. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ See incident history.

- ^ "GORP Mount Hood climbing description". http://www.gorp.com/parks-guide/travel-ta-mount-hood-national-forest-oregon-sidwcmdev_066522.html. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ Jack Grauer (July 1975). Mount Hood: A Complete History. self published. ISBN 0-930584-01-5.

- ^ Charles H. Anderson Jr.. "Deadly Fumaroles". International Glaciospeleological Survey. http://glaciercaves.com/html/mounth_1.HTM. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ "Ski Expert Dies In Crevasse". The Oregonian. March 2, 1969.

- ^ "Survivor of '76: If we made it, they can too". The Oregonian. 2006. http://www.oregonlive.com/news/oregonian/index.ssf?/base/front_page/116615670631000.xml&coll=7&thispage=1. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ Accidents in North American Mountaineering, 1981

- ^ a b c d Peck, Dennis (July 28, 2008). "Body recovered from dangerously steep area of Mount Hood". The Oregonian. http://blog.oregonlive.com/breakingnews/2008/07/climber_sparks_rescue_effort_o.html. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ "Doctors Remove Legs Of Mount Hood Climber". New York Times. May 19, 1986. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A0DE7DF1539F93AA25756C0A960948260&n=Top%2fReference%2fTimes%20Topi%20cs%2fSubjects%2fM%2fMountain%20Climbing. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "Climber Disappears". Oregon Mountaineering Association. 1995. http://www.i-world.net/oma/news/accidents/mt-hood-historical-summary.html.

- ^ "Fall on Snow, Climbing Along and Unroped". Oregon Mountaineering Association. 1998. http://www.i-world.net/oma/news/accidents/1997-05-19-hood.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Fall on Snow - Cooper Spur". Oregon Mountaineering Association. 1998. http://www.i-world.net/oma/news/accidents/1997-09-06-hood.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Mount Hood avalanche proves fatal for members of climbing group". Traditional Mountaineering. 2000. http://www.traditionalmountaineering.org/Report_MtHood_avalanche.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "Avalanche, Poor Position". Oregon Mountaineering Association. 1998. http://www.i-world.net/oma/news/accidents/1998-05-31-hood.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Robert Speik and Jed Williamson (2000). "Mount Hood Cooper Spur climb ends in tragedy". Traditional Mountaineering. http://www.traditionalmountaineering.org/Report_Hood_Cardin.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "Missing Hungarian Not Found On Mount Hood". Portland Mountain Rescue. September 8, 2001. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/hood090801.html. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "Snowboarder Dies on Mount Hood's North Face". Portland Mountain Rescue. May 24, 2002. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/hoodfatality052402.html. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "Three Dead, Many Injured on Mount Hood After Nine Climbers Fall and an Air Force Helicopter Crashes - PMR Coordinates Massive Rescue Effort". Portland Mountain Rescue. August 17, 2002. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/hoodbergschrund053002.html. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "Search for Missing Mount Hood Snowshoer Ends". Portland Mountain Rescue. March 7, 2003. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/hoodsnowshoe030303.html. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "PMR Joins Multi-Agency Search for Snowshoer's Remains - Body of Unidentified Person Found". Portland Mountain Rescue. August 3, 2003. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/hoodsearch080203.html. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ James, Karen (2008). Holding Fast: The Untold Story of the Mount Hood Tragedy. Thomas Nelson. pp. 256. ISBN 978-159-555-175-7.

- ^ "Hiker's Widow: 'We Know He Fought'". CBS. December 21, 2006. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/12/21/national/main2287407.shtml. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- ^ "Search for 2 climbers scaled back". Dallas News. 20 December 2006. http://www.dallasnews.com/sharedcontent/dws/news/nation/stories/DN-moreclimbers_20met.ART0.North.Edition1.3df9bd6.html.

- ^ "Rescuers find snow cave, equipment on Mount Hood". CNN News. December 17, 2006. http://www.cnn.com/2006/US/12/17/missing.climbers/index.html. Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ^ "Sheriff abandons hope of Mount Hood rescue". USA Today. 2006,December 21. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-12-20-mthood_x.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ^ "Small teams of searchers return to Hood". KGW. December 21, 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-01-20. http://web.archive.org/web/20070120063244/http://www.kgw.com/news-local/stories/kgw_121506_news_missing_climbers_friday.10a00d9b.html. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ "Saved Oregon climber: Rescuers 'were amazing'". CNN / Associated Press. February 20, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-02-22. http://web.archive.org/web/20070222080056/http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/02/20/missing.climbers.ap/index.html. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ "Oregon bill would require climbers to carry beacons". CNN / Associated Press. February 19, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-02-21. http://web.archive.org/web/20070221025116/http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/02/19/climber.safety.ap/index.html. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ "Stranded Mount Hood climbers were ill-prepared, rescuers say". Seattle Times. May 15, 2007. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2003706968_webclimbers14.html. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ "Two climbers (one injured) rescued". Portland Mountain Rescue. September 7, 2007. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20070907PearlyGatesRescue.html. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ "Overdue climbers found by PMR". Portland Mountain Rescue. January 14, 2008. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20080114OverdueClimbers.html. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ "Climbers Off Mountain After Night In Snow Cave". KPTV. January 15, 2008. http://www.kptv.com/news/15053663/detail.html. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ "Climbers Off Mountain After Night In Snow Cave" (video). KPTV. January 15, 2008. http://www.kptv.com/video/15060829/index.html. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ^ "Chris Biddle". Oregon Live. October 20, 2008. http://photos.oregonlive.com/oregonian/2008/10/chris_biddle.html. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ "Helicopter Lifts Injured Climber Off Mount Hood". KPTV. October 20, 2008. http://www.kptv.com/news/17757905/detail.html#-. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ "Injured Climber Released From Hospital". KPTV. October 20, 2008. http://www.kptv.com/news/17766392/detail.html#-. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ Rob Manning (October 21, 2008). "A Thankful Climber Recovers At OHSU". OPB. http://news.opb.org/article/3327-thankful-climber-recovers-ohsu/. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ "Climber Falls on Mount Hood". Portland Mountain Rescue. October 19, 2008. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20081019HoodFall.html. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ "PMR Rescues one of its own". Portland Mountain Rescue. January 17, 2009. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20090117PMROneOfOwn.html. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "PMR Recovers Climber's Body from Mount Hood". Portland Mountain Rescue. January 21, 2009. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20090121MtHoodBodyRecovery.html. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "PMR Assists with Climber's Self Rescue". Portland Mountain Rescue. February 1, 2009. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20090201DislocatedShoulder.html. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "Climber Survives 500-Foot Fall On Mt. Hood". KPTV. May 18, 2009. http://www.kptv.com/news/19485898/detail.html. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "Body found on Mt. Hood; 2 climbers still lost". USA Today. Dec 13, 2009. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2009-12-12-Oregon_N.htm?csp=34&utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+usatoday-NewsTopStories+%28News+-+Top+Stories%29&utm_content=Google+Feedfetcher. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ "Remains ID'd As Climbers Missing Since December". KPTV. August 26, 2010. http://www.kptv.com/news/24778636/detail.html. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ "PMR Assists at Coe Glacier". Portland Mountain Rescue. June 17, 2010. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20100617-CoeGlacier.html. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ "Body of Mount Hood climber recovered". KATU. June 17, 2010. http://www.katu.com/news/96615274.html. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ "PMR Participates in Rescue at Hot Rocks". Portland Mountain Rescue. July 7, 2010. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20100707-HotRocksRescue.html. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ "Coleman Headwall Mission". Portland Mountain Rescue. June 24, 2010. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20100724-ColemanHeadwall.html. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ "PMR Rescues a Stranded Climber". Portland Mountain Rescue. January 22, 2011. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20110122-PMRRescuesClimber.html. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ "PMR Assists in Rescue of Stranded Snow Boarder". Portland Mountain Rescue. February 20, 2011. http://www.pmru.org/pressroom/headlines/20110220-LostSnowboarder.html. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

External links

- Climbing Mt. Hood, including climbing conditions, from the Mount Hood National Forest website

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||